“There’s a difference between physical courage and moral courage. Which one should you possess?”

“Fear is a natural phenomenon. Like hunger and sex.”

What an outstanding talk!!!

“There’s a difference between physical courage and moral courage. Which one should you possess?”

“Fear is a natural phenomenon. Like hunger and sex.”

What an outstanding talk!!!

Pic: Paul Graham shot by Dave Thomas and shared under Creative Commons 2.0

I snitched this headline from the name a book. Hackers and Painters: Big Ideas from the Computer Age. If you haven’t read it yet, may I urge you to? It is a lovely book authored by Paul Graham, a computer scientist, venture capitalist and well, a writer. And if you’re among those not inclined to read a book, he captured the sum and substance of it all in an essay back in 2003.

Some lovely learnings emerge out of it on what comprises the hacker ethic, in which he underlines the significance of relentless practice, devotion to beauty, why a premium ought to be placed on disciplines we are unfamiliar with, the humility to try and imbibe from others what we don’t know of, and above all else, inculcating a habit that allows us to share and collaborate so that we become lifelong learners.

Philosophically, it influenced many in computer science deeply. Because that is where he was best known and enthusiasts—or hackers, as they were called then, when the word wasn’t as bastardized—were enthused by his ideas. They could see the value in what he proposed. When I came of age, I could see merit in his ideas and was among those who embraced them.

But personal philosophies are malleable and susceptible to influences. That is why, at some point, I started to question the premise. I argued against the most beautiful of his ideas—collaboration.

“Maybe, I’m not a nice guy. I don’t care," I wrote once. Friends who knew me as a technology enthusiast and someone who had benefited from it were appalled at what they thought was a complete misunderstanding of a powerful idea. In a scathing indictment, I was told, “the most unfortunate thing is that we have journalists like you..."

In hindsight, I suspect I may have felt insecure with the idea of sharing. Because at the end of the day, my livelihood, I thought, is a function of the ideas and the words that came out of what I think up and my networks. How can I possibly give it away for free?

That is why, I argued, “by thinking something up and offering it to the collective to improve upon, I stand to lose my livelihood... it leaves me with no incentive to write". Therefore, I ought to do all I can to protect what I come up with.

But much experimentation, conversations and learnings later, I now concede I was wrong. I stand corrected and an apology is in order. I admit the world we live in now wouldn’t have gotten to where it is without collaboration.

So much so that even Microsoft, the bastion of all things proprietary, after having fought to keep the world out of its doors, is now seeking to collaborate. Otherwise, it knows, it will perish.

So, who are hackers and how did hacks get into the lexicon? Everybody, it seems, is into hacking. Computer hacks, study hacks, sleep hacks, food hacks and, to top it all off, life hacks.

To put that into perspective, let us first understand what a hacker is not:

Geniuses who write books on “ethical hacking" and sell courses on “ethical hacking" are, well, geniuses. Because it needs a genius to find a market full of idiots willing to pay money to become a “certified hacker". None of what Graham articulated needs to be certified. It is a world view.

Then there are management gurus who take terms like jugaad—a word most north Indians are familiar with. Loosely translated, a quick fix or, well, a “hack" as it is now understood. Packaged for the West and management schools, it is rephrased and given a lovely twist—frugal innovation.

By way of example, think of a contraption like the jugaad which plies on north Indian roads. The handle of an old scooter, tyres and engine of a motorcycle, the frame of a bicycle, the body of a bullock cart and a diesel engine to are retro-fitted to create a dangerous contraption.

This is then deployed on the roads for pretty much everything from ferrying people to livestock and goods. It does not fall under the ambit of the Motor Vehicles Act. It is jugaad, and fits the framework of “frugal innovation".

But two problems exist here.

It cannot be scaled.

It violates the law because it is a safety hazard. So much of a hazard that the Supreme Court had to intervene and has asked all states where such vehicles ply to provide the court with details of what authorities are doing to take these contraptions off the road.

My limited submission here is that the Hacker Ethic in its purest sense is not about finding shortcuts like these.

Instead, it focuses on finding truth, purpose, beauty, meaning and goodness in an optimum manner. And like I said earlier, this ethic insists we place a premium on optimizing ourselves and our work, so that we can devote as much of our time as we can to learn.

How? Allow me to provide a few instances:

The other day, I stumbled across an interview of Mark Zuckerberg, the billionaire co-founder of Facebook. The 25-minute interview in which he articulated all of his ideas revealed clarity in thought. But what struck me was something else altogether. While in college, he studied both psychology and computer science.

In India, this is an alien idea. The way things are, computer science is kosher because it can potentially make an engineer out of you. Psychology is not because it falls in the domain of liberal arts.

To cite but one instance, while talking with a doctor the other day, I asked him what his son was up to. He told me the original plan was to get the young man to pursue a career in medicine. But if he doesn’t get through the exams, “let him do arts or some shit".

The tone was not condescending, but one that smacked of downright derision.

Hackers sneer at people who speak this language. That is why Zuckerberg studied psychology. All thanks to it, he could ask, “What is it that people want the most?"

His understanding of the domain taught him that humans seek other people out the most. What he learnt at his computer science class helped him create a software platform that could take his understanding of the human mind into a place he would otherwise not have been able to if he were wedded to either one of the disciplines. In his head, the disciplines collaborated.

Having done that, he sought out people who understood the other arts, like design, and domains like business to build what is now one of the most formidable entities in the world. He optimized himself by collaborating between disciplines and others.

Then there is this nonsense I come across every other day about how large organizations are trying to “replicate the start-up culture". And to do that, they have begun by “breaking down silos". This includes doing ridiculous things like spending obscene amounts on creating “open offices".

Apparently, “open offices" facilitate conversations and an “open culture". Who is to tell them the Hacker Ethic includes an idea called Deep Work? And that there is evidence that conclusively demonstrates open offices are actually an insanely stupid idea because they kill productivity?

This is because, to get meaningful work done, the human mind needs to find the optimal state to be in—the Flow, as defined by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. Most people call it as “being in the zone". To get here, they need their space.

But organizations, in attempts to ape Facebook or Google without understanding the ethic that drives them, compel people to operate under suboptimal conditions. Zuckerberg didn’t start out trying to build a company. Neither did the founders of Google. They started out by trying to solve problems that real people face.

To do that, they worked with the resources they had on hand. Which is essentially what a start-up is. That profitable entities came out of it is another story altogether.

But in trying to replicate start-up cultures, you cannot force-fit the Hacker Ethic into it. The most charitable thing that can be said of such attempts is that it is a horribly atrociously version of jugaad. It is destined to fail.

And why will they fail? Because hackers share. They work with the collective. By way of example, take the Human Genome Project (HGP). It is the world’s largest collaborative biological project, conducted across 20 universities and research centres and funded by the governments of the US, UK, Japan, France, Germany, Canada and China.

The database is there for anybody to access on the Internet. When looked at in isolation, the database can be gibberish because the quantum of information in it is so huge, it is impossible for any single entity to make any meaning out of it. Unless individuals and organizations collaborate to make meaning out of it for the greater common good.

Are there profits to be made out of it? Most certainly. Businesses have come to build around the ecosystem that is the HGP and provide highly personalized services to individuals across the world. The system is still evolving and who knows what may come out of it?

Now, this ought us to introspect and ask: Am I a hacker? Let’s put it this way. If you think of the Hacker Ethic as a way of life, then yes. It isn’t always about coding and computers alone, but about looking at the wisdom they have gained and trying to emulate it.

They don’t seek shortcuts. They seek elegant solutions to complex problems. When wrong, they have the humility to admit that they were in the wrong, move on and find the next optimum. They seek, they search, they look for the best ideas and they share as openly as they gain. This ethic is a life of learning, adapting and not scrimping.

This piece was first published in Mint on September 17, 2016

Image under Creative Commons

Contrary to what I always imagined, the ambience outside the intensive care unit, or ICU, where my dad sleeps now isn’t antiseptic. Around me are a few chairs, and a few weary faces. Pretty much everybody is glued to mobile handsets. The only time they come to life is when one of the security personnel shouts out a number. The guardian of one of the human beings admitted in the ICU then jumps up and scrambles to do whatever it is that the resident medical officer (RMO) or nurse in charge wants them to.

The only times I have seen my dad are when the number he is now identified by is shouted out. I haven’t been allowed in any place close to him since he was wheeled into the emergency room earlier today. Since then, he has become just another body that lies sedated in a sterile environment, in sharp contrast to the air outside. I don’t know what will become of him when he gets out of there. The doctors in charge claim they don’t know either. “Under observation for 48 hours," is all they mutter.

*****

I think it was yesterday. Or at least it seems like that. The two sons of a junior warrant officer (JWO) in the Indian Air Force (IAF) and his wife would walk the lanes and bylanes of Sion, a suburb in Mumbai, every evening.

At some point, the young officer would strike a deal with his sons. Either they could stop by a street vendor who hawked comics where they could debate and deliberate further on which title of Amar Chitra Katha they ought to settle on, or whether they’d much rather everybody share a plate of vada sambar or masala dosa at Hanuman Restaurant right across where the vendor sat. The only times there was no debate was when the latest copy of Tinkle hit the stands.

At all other times, the officer was clear it had to be either the comics or the food. Certainly not both. The boys resented it because they thought they were being disciplined into making choices. The young officer made it sound that way while the mother looked on indulgently. More often than not, the comics won over the food.

Purchases done, all of them would troop home and the young man would lie on his bed, open the comic, the boys on either side, and he’d animatedly read out tales from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, Valmiki, the Jataka Tales, and every once a while stories of heroes from contemporary Indian history that Amar Chitra Katha thought appropriate to publish.

The older boy grew to become me—a journalist; the younger one, my brother, a researcher in the neurosciences. Thirty-five-odd years down the line, in hindsight, the both of us know the young officer wasn’t trying to teach his sons to choose. It was because a JWO in the IAF then barely took home enough money to make both ends meet.

We grew up in an India where “India was Indira and Indira was India". My folks hadn’t heard of economic liberalization and its potential benefits until the early 1990s. Not that it made sense to them. But by the time they did and figured out what it meant, their boys were ready to join the workforce. Until then, the only kind of parenting most middle-class folks like them knew was to give their boys the best, like buying comics pretty much every other day. If that meant mortgaging little pieces of gold at the local pawn shop from our mother’s meagre dowry, then that is what they did.

But something happened, a mutation if you will, between generations. The kindness and genteel parenting dad weaned us on got replaced by “helicopter parenting" of the kind my generation and I practise.

My older daughter Nayanatara doesn’t have the time for long walks with me. Just out of Class IV, her mornings are crammed with a ruthless curriculum that leaves no room for simple joys like Uncle Pai in Tinkle. When done with her formal class hours, she attends classes for taekwondo, kathak, phonics (which will apparently do her diction good), quilling, art and pottery. My wife and I think it par for the course if she has to grow up into a well-rounded individual.

My folks aren’t so sure. They think their kids—my brother and I—turned out to be reasonably decent blokes given the Rs. 400-odd the IAF paid my dad every month by way of salary. I suspect they may just have a point.

Each time dad tried to tell me that gently, I’d go into a funk and tell him the times have changed. But as he convulses yet again, the RMO tells me they’re at a loss, and that the ventilator sounds the most plausible option—someplace in my head tells me I ought to consider his advice on parenting a bit more seriously. It’s okay to let children be and soak life in without imposing the ideals of what adulthood ought to be like on them. They’ll just turn out fine. So long as you have the bandwidth to attend to their simple needs—be a playmate when they need you and read a few comics together every once in a while.

*****

The kind of literature on medicine I have read includes the compassion of Atul Gawande, the eruditon of Sherwin Nuland and the perspective of Roy Porter. Their expositions on the practice offered me stunning insights into the relentless world of young resident doctors, the nature of how we biologically live and why our cells die. That is why I always thought of medical practitioners as romantic ideals.

But in the real world, across the glass wall where dad lies right now, Gawande and Nuland and Porter are just that—romantic ideals. The resident doctors are—pardon my expression—kids on whom the graveyard shift is an imposed one. They are trying their damndest best to do what the textbooks have taught them. But experience is still to mentor them.

Over time they will morph into seniors, like the ones doing the rounds now, and who during their normal waking hours are arrogant pricks. Pardon my expression, but there is no other way to describe them. Allow me tell you why. Fed up of the “He’s under observation" line, I thought up a quick one to throw at the senior doctor on the rounds.

“Excuse me sir, but which lobe of his is affected?"

“You understand medicine?" he asked me condescendingly.

“I’m a practising biochemist," I lied through my teeth.

“Ah! You’re one of us," he melted and proceeded to take me through the initial prognosis.

Much of it sounded like Greek and Latin. But because curiosity had compelled me to read Gray’s Anatomy and some textbooks on biochemistry closely in the past, and carry an app called HealthKart on my phone that I look up every once a while to understand the nature of various drugs, I managed to nod intelligently, ask some questions, and finally get a fix on what is happening to dad.

Perhaps I am being unduly harsh on the fraternity. When looked at from one perspective, how can an overworked medic sit down and possibly explain the nuances of medicine to traumatized caregivers clueless about the machinations of medicine?

I can think of exceptions to the rule like the good Dr Natarajan, an obstetrician, who devoted patience and time to my wife and me when we’d gone through a scare a long time ago when she was carrying our second child. He assuaged our concerns and treated us like humans—not like preserved tissue samples in formaldehyde jars that reside in medical schools. That said, I maintain that the likes of him are exceptions.

But why should it be? If kids weaned on comic books purchased on the back of wafer thin pay packets and mortgaged gold can grow up into informed individuals, what makes medical professionals think they can be condescending? I buy the argument that they soak in an enormous amount of pressure. But what if these medics were put into the pressure-cooker environment that is the newsroom; or a trading room at a broking outfit; or asked to frame policies that rein in the fiscal deficit? None of these professionals can get away without explaining the nuances to the masses. Because if they don’t, they’ll get lynched.

Why did I have to lie and claim I am a biochemist to understand what’s going on? Why did their doors open warmly only when my brother, who is actually a doctor, walk in? What if I hadn’t lied? What if my brother wasn’t a doctor? Much like the weary souls splattered across chairs outside the waiting room, I’d be groping in the dark and be on tenterhooks.

The problem with the practical medicine that exists in hospitals outside the books of Gawande, Nuland and Porter is that they don’t understand the nuances of what it means to be human. It lives instead in a cloistered world seeped in arrogance.

The other problem with contemporary medicine—and by that I mean allopathy—is that it exists in silos. There are neurologists, cardiologists, urologists, pathologists, pharmacologists and so on and so forth. Each of them has a microscopic understanding of the microcosm they work on in the human body.

A good general practitioner (GP) with a holistic view is practically impossible to come by. Contemporary allopathy has, for all practical purposes, killed the GP. Philosophically, Ayurveda espouses the idea of holistic medicine. But it is hopelessly outdated. In times of crisis, it is not a science that can be relied on. The way it is now, it is but a body of ancient texts that practitioners turn to. As for homeopathy, anybody who thinks it a science ought to be an idiot. How am I to take any system that believes in the placebo effect seriously?

Where does this leave us when faced with a crisis but to turn to a splintered system like allopathy? For all of its frailties, at the end of the day, it has done more to extend our life spans than any other system.

Now, if only it could temper the arrogance its practitioners come with!

*****

Dad thought it only appropriate he marry my mum when he first set his eyes on her. He was 22. She was 20. Her old man, my grandfather, was scandalized in what was then a very traditional Malayali society. He tried to talk the young man out of it. But dad firmly declined. She was his first girlfriend. He was her first boyfriend. They’ve been married 45 years now. Neither will eat a meal without the other. Nor will they end the day without having reported to each other all of what they did during the day.

I always thought this an old-world relationship that is pretty much impossible to sustain in the world we live in now. I’ve had conversations in the past with friends who practise psychology. Their hypothesis is easy to comprehend.

We live terribly busy lives. Not all of our needs can be satisfied by one individual. So, in theory, it is not just probable, but okay to seek multiple partners so that all of our needs are satisfied. To that extent, I am told many practising psychologists believe adultery is kosher—and that over time, the mainstream will come to accept it.

During one of my long walks with dad, I asked him what he thought of the hypothesis. He laughed gently, as is his wont. “Your mother meets all of my needs," he told me then. “I haven’t looked at another woman, ever."

“You won’t understand how we love," mum once told me.

That is why, even as his sedated mind now groans out for her, she watches stoically from the other side of the glass door. There is nothing she can do but hold his hand in the brief moments they allow her to.

A wall of silence separates mum from both of her sons. Her front is brave. But deep down, I guess she needs to talk to somebody. But that somebody lies in a mist. What will happen of their 45-year-old love story if he isn’t around? What will happen of her if he isn’t around to pamper and drive her around? I don’t know.

I wish that I knew how to love like he loved—the good, old-fashioned way—devoid of all pretences.

He tried his damndest best to teach us that through Amar Chitra Katha so we understood how to love our spouses in much the same way that Satyavan did Savitri, so that when Yama, the god of death, comes calling, death can be cheated.

As I wind these dispatches up, I wait and watch quietly, hoping Satyavan will indeed wake up from the deep sleep he is in now, beat the odds that Yama has placed on him, and walk back home to the Savitri he loves so much.

“We’ll keep him under observation for 48 hours," I’m told again and am jolted back to reality.

This piece was first published in Mint on Sunday on May 30 2015

Because we’re fed on clichés such as ‘Strive to make every day a masterpiece’, it is inevitable that most of us feel despondent at times like these. Despite starting out with the best intentions, our days become monotonous because we’re locked down. It is only human to think about what can be done to escape that monotony.

But examine history and you see that monotony appears to be inherent and essential to the human condition. In fact, humanity has progressed on the backs of those who embraced monotony and imagined it as a series of elaborate rituals.

By way of example, Isaac Newton was most prolific when everyone was quarantined at home during the Great Plague of 1665. He used the time alone to think about differential and integral calculus, formulated a theory of universal gravitation, and explored the nature of optics by drilling a hole in his door and studying the beam of light it let in. How much more beautiful can the human mind get?

In a more recent context, consider something as monotonous as the washing of hands. It has now been imposed on us. What can possibly be exciting about something as monotonous as that?

Well, when looked at through the eyes of award-winning writer Atul Gawande, if not done right, it can take those whom he examines closer to death in his day job as a surgeon. In his book, Better: A Surgeon’s Notes On Performance, he points out, all research and his experience articulate strict protocols physicians must adhere to while performing what sounds like a perfunctory act.

Turns out, a hand wash with plain soap can reduce bacterial count, but this isn’t good enough. To wash well, an antibacterial soap is needed. But to wash hands the right way, all external objects such as a watch or ring must first be removed. Following which the hands must be held under warm water for a few moments. Soap must then be dispensed and lathered on the hands and lower one-third of the arms for 15 to 30 seconds. The hands must then be rinsed for a full 30 seconds in warm water and dried with a disposable towel. Only then is the act of washing hands considered complete.

Now, this begins to sound like an elaborate ritual. Failure to engage in this ritual can spread infections and cause death. When this ritual is examined closely, there is purpose to it. Done well over the long term, it can make the difference between life and death, many times over.

All evidence has it that washing hands well is currently our primary weapon against the coronavirus. What does that imply? That we should accept that life will sometimes be monotonous. But we can me make that monotony worthwhile by examining the little details inherent in it, and turning practice to perfection, deliberately.

This article was first published in in the Sunday edition of Hindustan Times

Image by Zoutedrop under Creative Commons

Dear 16-year old self,

At 47, I have no pretensions of being a wise man. Because as Hunter S. Thompson, that godfather of gonzo journalism, whom I worship, wrote so eloquently: “To give advice to a man who asks what to do with his life implies something very close to egomania. To presume to point a man to the right and ultimate goal—to point with a trembling finger in the right direction—is something only a fool would take upon himself."

That said, I couldn’t help but think of what my friend Dr. Rajat Chauhan keeps articulating in so many different ways. The other day, for instance, he tweeted, “Failure is inevitable. It’s about having the persistence to beat the pulp out of failure."

It got my attention and I asked him to make a signed poster out of it that I may frame and keep in my room.

That is why I know what you feel right now. With the kind of scores you have managed in Class XII, you will never make it to medical school. I know you want to go there real bad. So, it’s okay to cry. And feel those tears running down your face. I want you to hurt. Not just hurt, but hurt real bad. I want you to embrace failure, make it your best friend, and learn from it.

That said, there are three instances I want you to particularly fail in as you grow up—love, friendships and work.

I understand I may sound ridiculous to you right now. But let’s face it.

That object of your affection whose hand you hold right now exists only in fairy tales. Even as she consoles you and tells you the both of you can carve a life out in some pretty corner of the world, don’t forget you are only 16, much like she is. Don’t hate me for saying this. What you are experiencing right now is puppy love. I am not suggesting here you ought not to experience it. Everybody ought to. But it won’t last. You know why?

Because right now you are in love with the idea of love. I wish I could explain that as eloquently as John Steinbeck, one of my favourite writers, did in a letter to his son: “There are several kinds of love. One is a selfish, mean, grasping, egoistical thing, which uses love for self-importance. This is the ugly and crippling kind. The other is an outpouring of everything good in you—of kindness and consideration and respect—not only the social respect of manners but the greater respect which is recognition of another person as unique and valuable. The first kind can make you sick and small and weak but the second can release in you strength, and courage and goodness and even wisdom you didn’t know you had.”

It is a rare set of individuals who find the second kind of love when they are as young as you are.

So, I want you to go out there and get your heart broken a few times, until you find that somebody who can extract goodness out of you—of your own free will. Trust me, the road to finding this kind of love is a painful one. It is inevitable the one whose hand you are clinging to now will move on as will you. It is also inevitable you will find true love. But brace yourself for heartbreak on the way to it.

Because, as David Whyte writes in Consolations, “Heartbreak is how we mature; yet we use the word heartbreak as if it only occurs when things have gone wrong: an unrequited love, a shattered dream… But heartbreak may be the very essence of being human, of being on the journey from here to there, and of coming to care deeply for what we find along the way…. There is almost no path a human being can follow that does not lead to heartbreak.”

And when you do find love, respect it and cling to it.

Much the same can be said of friendships. It is a myth that deep and meaningful relationships are forged in your formative years. The fact is, over time, you outgrow them. The friends you have in your teens are very different from the ones you have in your 20s, 30s and 40s. As you search for meaning, with every decade, you will morph into a different animal and will seek bonds that fit the animal you are then.

By way of example, I can think of this gentleman I met the other day, now in his 60s. There was nostalgia and tears in his eyes as he reminisced about his friend from 40 years ago who sought him out for counsel every other day. Time changed things between them. His friend has gone on to larger things and doesn’t need his counsel any more. His attention has turned instead to others with a larger perspective whom he looks upon with awe and seeks out.

I understand the tears and the nostalgia. But they are rooted in the past. You swear now by friends who roar to Metallica and Guns N’ Roses. But trust me . When you discover the pleasures of Paul Simon, the serenity of Beethoven and the comfort good single malts offers over Old Monk rum, you will wonder how you air-guitared at alcohol-soaked, pot-filled concerts all night long.

And while I am at that, another word of advice from a now world-weary man—never, never touch a cigarette a friend offers. It may seem cool and you may look like a wimp if you decline. But the real wimps are the ones who smoke. I know. I’m still paying the price for having indulged in it.

When it comes to work, there is this tussle you will be engaged in. Allow me to assure you once again, like most people, you are destined to fail if you don’t give yourself the room to think through and introspect. Who do you want to be? What is your calling? What are your priorities?

But the exigencies, such as money, that life imposes will push you towards a path often trod by most people. Like I did when looking for a job. Entrepreneurship wasn’t my calling. It was an accident. That it turned out to be a lucky accident and eventually my calling is an altogether different matter. It is entirely possible, though, that you may not get as lucky. That is why I want you to dwell on this passage from The Road to Character by David Brooks.

“I’ve been thinking about the difference between the résumé virtues and the eulogy virtues. The résumé virtues are the ones you list on your résumé, the skills that you bring to the job market and that contribute to external success. The eulogy virtues are deeper. They’re the virtues that get talked about at your funeral, the ones that exist at the core of your being—whether you are kind, brave, honest or faithful; what kind of relationships you formed.

“Most of us would say that the eulogy virtues are more important than the résumé virtues, but I confess that for long stretches of my life I’ve spent more time thinking about the latter than the former. Our education system is certainly oriented around the résumé virtues more than the eulogy ones. Public conversation is, too—the self-help tips in magazines, the non-fiction bestsellers. Most of us have clearer strategies for how to achieve career success than we do for how to develop a profound character."

My final submission to you is, the earlier you can think of a eulogy to yourself, distanced from the exigencies of life I spoke of earlier, the better off you will be for it.

Much love,

Your 47-year-old future self

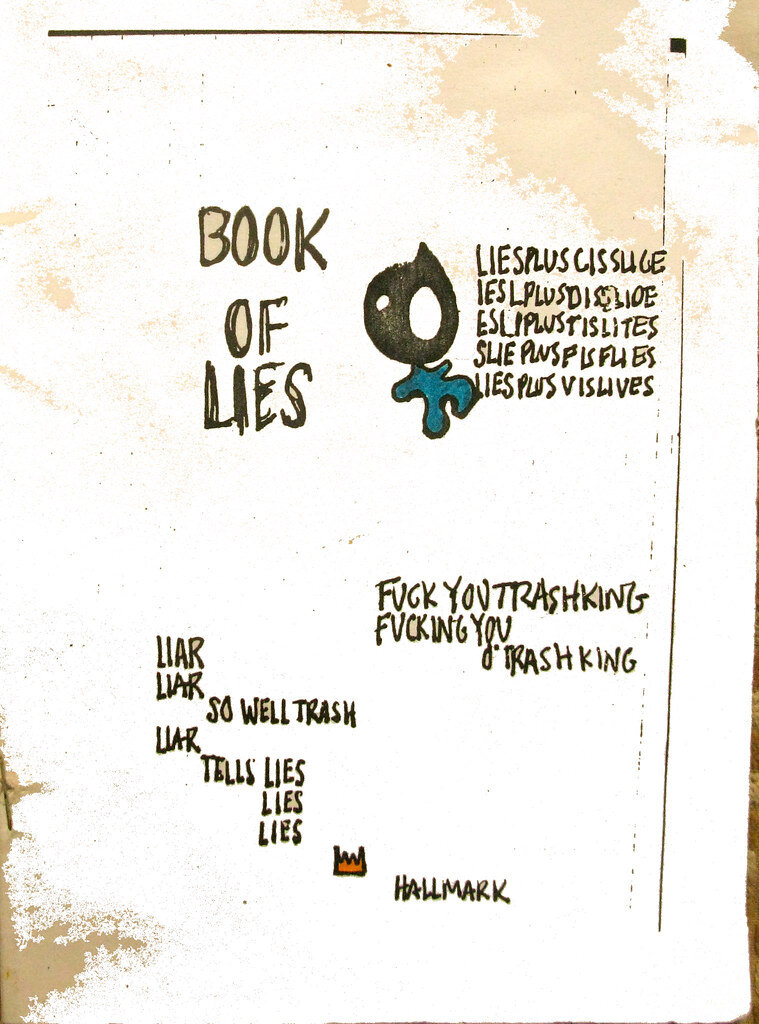

book of lies © 1992, scott richard (cover) Image Under Creative Commons

A little before I sat down to write this piece, I saw a headline that screamed: “I never lie”. It featured someone from the advertising business. I couldn’t help but snigger. What’s wrong with a lie, I wondered.

Indeed. It is a question that has resided in our collective human conscience forever. So much so that it resides as one among the central themes of that philosophical tour de force the Mahabharata is—an epic narrative of the Kurukshetra war and the fates of its protagonists that comprise two warring clans, the Kauravas and the Pandavas.

In the epic, there is this part where one of the greatest warriors of all time, Drona, is on a rampage through the Pandava ranks. Related to both sides as an uncle, for various reasons, he chose to align himself with the Kauravas in this battle. If he isn’t stopped, the Pandavas fear it is only a matter of time before their army is in shreds. The oldest of the five Pandava brothers, Yudhisthira, then turns to their spiritual and philosophical mentor Krishna for counsel.

Krishna, the eighth avatar of Vishnu, the supreme god, tells Yudhisthira this is a war that must be won. And that if a lie ought to be told to win it, then the lie must be told. In this instance, Krishna knows Drona’s only weakness is his son Ashwathama. So, he asks Yudhisthira to spread the word that Ashwathama is dead. But Yudhisthira has a problem with that. His morality and reputation do not permit him to lie. He despises it as dishonest.

But even as Yudhisthira is thinking through Krishna’s proposition and its implications, Bhima, one of the Pandava brothers, kills an elephant named Ashwathama and screams: “Ashwathama is dead”. Word reaches Drona. The man thinks it is his son Bhima is talking of. Stunned, he refuses to believe the news until he hears it from Yudhisthira and summons him.

Krishna’s words still ringing in his ears, Yudhisthira goes over to his uncle’s camp.

“Is it true,” Drona asks him, “that Ashwathama is dead?”

“Yes,” Yudhisthira says. And then trails off inaudibly, “Ashwathama the elephant.”

Technically, Yudhisthira did not lie. But Drona doesn’t catch the words, lays down his weapons and bows his head in grief. In that very instant, on Krishna’s instructions, Dhrishtadyumna, Yudhisthira’s brother-in-law, chops his head off.

In Vedic society, this is the worst possible crime. The Pandavas killed an unarmed Brahmin on the back of subterfuge who in their younger years was a teacher to them as well. But it had to be done for the sake of “dharma”, argues Krishna.

When looked at from Krishna’s perspective, it makes sense. All of the brothers are killing each other, too many people are dying and the war has to end in everybody’s interest. To that extent, morality demands that Yudhisthira lie. The end, in this case, argues Krishna, justifies the means. Psychology has it that Krishna makes this call without compunction because he is emotionally more evolved.

This argument though has always been under scrutiny with much being written and debated around it. The founding fathers of the Christian church like St Augustine make it abundantly clear that a lie is a lie, no matter what the intent is. Western philosophical thought led Immanuel Kant and closer home Mahatma Gandhi find their moorings in this school of thought. They leave no room for a lie in any shade. And that is what we are taught to live by.

As Michael Sandel, who teaches philosophy at Harvard University, points out, Kant believed that telling a lie, even a white lie, is a violation of one’s own dignity. But do exceptions to the rule exist? When is ambiguity possible? For instance, if your friend were hiding inside your home, and a person intent on killing your friend came to your door and asked you where he was, would it be wrong to tell a lie? If so, would it be moral to try to mislead the murderer without actually lying?

This question has implications in modern-day business as well. In a paper published last year titled Are Liars Ethical, Maurice Schweitzer, a professor of operations and information management at Wharton University, and co-author Emma Levine veer philosophically to Krishna’s side.

The video of a conversation with them can be viewed here. The sum and substance of their argument is this: “We look at deception that sometimes can be helpful to other people. We typically think about deception as selfish deception: I lie to gain some advantage at the expense of somebody else. And we typically think of honesty as something that might be costly to me, but helpful to others.”

“In our research, we actually disentangle those two things. We think about deception that can help other people, and honesty that might be helpful to myself and maybe costly to somebody else. When we separate honesty and deception from pro-social and pro-self-interests, we find that people actually don’t care that much about deception. We find that the aversion to lying, when people say ‘Don’t lie to me’, what they really mean is, ‘Don’t be really selfish’.”

To that extent, they argue that in the kind of world we live in, it is time to revisit the dictum: Honesty is the best policy. Instead, we ought to understand when we should lie. “When does honesty actually harm trust and seem immoral? And when can deception actually breed trust be seen as moral?”

The reason this is pertinent is because in business, managers have to balance between benevolence and honesty, where benevolence is about being kind and providing supportive feedback. Honesty, on the other hand, can be critical and harsh. Not everybody is built to handle honesty. To that extent, it makes sense to err on the side of benevolence in the longer-term interests of building trust and relationships.

Schweitzer and Levine studied the tension between honesty and benevolence under controlled conditions that it may be applied in business. Their findings make for a compelling read.

“There are a lot of domains in which individuals face this conflict between honesty and benevolence very, very intensely. One example is in healthcare. Doctors frequently have to deliver very negative news to patients. And actually, prior research has found that oftentimes, doctors do lie. They inflate the positivity of these prognoses. We seem to think this is bad, and I think doctors feel a lot of tension and conflict around how to handle the situation.

“But our research suggests that perhaps doctors, and maybe teachers and parents, should be explicitly acknowledging this tension and this trade-off, and thinking about and talking about how to navigate it. When might benevolence and kindness, and maybe a little dishonesty, be right or be appreciated, and how could that enhance the delivery of medicine?

“Another case where we manage this balance between being completely honest and managing being benevolent is when we interact with children. This is true as parents, and it’s also true as educators. So, teachers will need to give feedback to students. And they have to balance this tension between being completely candid, and being benevolent and kind—demonstrating kindness and concern for the child.

“As parents, we frequently tell our kids, ‘Never lie’. But that’s not at all what we mean. For example, before we go over to grandma’s house, we might tell them, say, ‘Remember, thank grandma for that sweater, and tell her how much you like it, even though we both know you never wear it’.”

This is the kind of ambiguity and tension Krishna nailed with precision almost 3,000 years BCE when the Mahabharata was written.

But who’s to tell that to the man in advertising who claims he never lies?